Blogs

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020. All the continents except Antarctica have so far reported thousands of coronavirus cases and/or deaths. Globally, more than a million cases have been reported with 24% of deaths affecting a broad range of ages. Africa has been lucky to have a delayed onset of the spread of COVID-19. The continent has had the benefit of time to learn from measures and contingencies that are working in other countries. However, there is need to take caution not to generalize and mirror policies being implemented in other places without consideration of Africa’s unique context i.e. demographic structure, population, disease burden health care systems, and living conditions.

Globally, coronavirus has spread rapidly and countries are using various measures to curb the pandemic disease. These measures include complete and/or partial lockdowns, shifting to remote working, online schooling, promoting hand-washing, and social distancing. Seemingly, many countries have adopted lockdown policies where majority of citizens are advised to stay home and prepare for what could be months of isolation and social distancing. However, some of the recommended measures are not practical in the African setting because of various reasons. For instance, a significant populace lives from hand-to-mouth relying on daily wages, and total lockdown means no food. Also, Internet access is so limited that working remotely or online schooling is not possible for majority of the population.

COVID-19 could bring Africa’s weak health systems to their knees

Coronavirus has so far spread to over 39 African countries within weeks, reaching 8000 cases and 334 deaths. For the few countries that have not reported any cases, there are concerns that the absence of cases is as a result of lacking or weak testing capacity. WHO is supporting African governments with early detection by providing COVID-19 testing kits, training health workers, and strengthening surveillance in communities. 47 out of 54 countries in the WHO African region can now test for COVID-19. For instance, Nigeria and Togo among other West African Counties can test 1,500 patients each day. Early detection of cases is one of the measures of curbing the spread of coronavirus as it allows coronavirus-infected patients to be separated from non-infected people.

Experts are worried about COVID-19 rapidly spreading in Africa and numbers rising to those recorded in countries such as China and Italy. A major concern is the fragile health systems in most African countries that often suffer from minimal or no medical supplies and equipment, inadequate funding, shortage of adequately trained healthcare personnel, and inefficient data transmission and use. These weak health care systems are currently overburdened by diseases such as malaria, HIV, tuberculosis, cholera, cancer, diabetes, and maternal and child health issues. Clearly, these systems currently have no capacity to deal with COVID-19. Experts therefore fear that the pandemic could be difficult to manage in Africa, and could cause huge numbers of deaths and grave economic problems if it spreads widely.

African countries must learn from own experiences of managing Ebola, polio and cholera

In the last three years, Africa has had significant experience having dealt with different epidemics like Ebola, polio and cholera. Hence, drawing lessons learnt on preparedness and response to previous epidemics is crucial in enabling African countries develop effective strategies to curb the spread of COVID-19. For example, there is undocumented evidence that Taiwan and Singapore took quick drastic measures to curb COVID-19 due to their experience with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). Active surveillance network, among other, measures helped to control and prevent massive spread of the disease epidemics in their countries. Documenting evidence on the lessons from African countries that experienced and addressed Ebola could also be valuable in designing country responses to COVID-19.

A strategic approach is critical for African governments to combat this COVID-19 pandemic. For Africa considering her unique context, the strategy should focus on prevention and containment. Indeed, African governments can borrow valuable lessons from other countries who had earlier exposure with coronavirus such as Italy and China. However, strategies and possible solutions of managing COVID-19 cannot just be generalized to African countries. This is because these strategies and solutions have been mostly implemented in high-income countries and may not necessarily work for Africa because of her unique contexts.

the high levels of poverty in many African countries means that large proportions of African populations live on daily wages. Complete lockdown directives pose serious challenges unless governments are ready and able to provide food… Click To TweetTo begin with, the high levels of poverty in many African countries means that large proportions of African populations live on daily wages, which means complete lockdown directives pose serious challenges unless governments are ready and able to provide food provisions to the most vulnerable. Secondly, there is the issue of poor living conditions for large of proportions of populations in many African cities due to informal or slum settlements. Managing and preventing Coronavirus is likely to be particularly grave in urban informal settlements, which lack access to running water, people live in crowded housing structures and conditions, and poverty levels are rampant. These living conditions mean that the strategy of social distancing and self-quarantine may not be feasible. Similarly, many parts of rural Africa still do not have access to running water. For such communities, the intervention of constant hand-washing may not be feasible. Thirdly, there are also large displaced populations due to war and instability living in refugee camps in different parts of Africa. The conditions in these camps also mean that much of the strategies that have been applied in high income settings are unlikely to work in these settings. In most of these settings, interventions must go beyond sensitizing people to wash hands to offer practical assistance including setting up hand washing points and providing hygiene and sanitary facilities. You will not be surprised to find one toilet being shared among over 50 households in some informal settlements.

Evidence is key

Over and above, African countries need context-specific evidence to inform how they adapt global solutions being put forth to contain the spread of the virus, or to help them come up with their own unique solutions that can work within their contexts. Yet, unlike high income countries that have quickly dedicated resources to generating quick scientific evidence and solutions to COVID-19, African governments, amid limited resources, have not dedicated much resources to generate context-specific scientific evidence and solutions. Therefore, it is vital for the experts to provide lessons that African governments urgently need to inform the policy decisions they are making and implementing in response to COVID-19.

Certainly African leaders need evidence from African contexts and other similar contexts to provide practical policies and programmatic solutions to COVID-19. This context-sensitive evidence needs to inform the adaptation of global solutions to COVID-19 so that these are more responsive to Africa’s unique context. In most African countries, however, the institutional systems and structures that can readily provide such locally relevant evidence are either weak or missing altogether. For instance, there are no existing evidence review and synthesis centres supporting policy decisions being made by ministries of health. At best, these ministries rely on university departments to provide the research needed, or have medical research institutes (such the Kenya Medical Research Institute for Kenya) that are mandated to provide research needed for health sector decision-making. Even then, these university departments or medical research institutes receive very minimal funding from governments that in many cases they are unable to provide the research needed for health sector decision-making.

This is partly the reason why many African countries are simply replicating global solutions to COVID-19, with minimal adaptation of these because the local evidence needed to help adapt the global solutions is missing. In some cases, these governments are also not reaching out to local scholars and institutions to provide the evidence they need to adapt global solutions to Africa’s contexts.

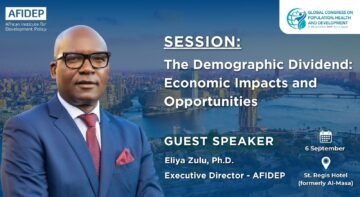

The African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP) is currently contributing to addressing the weak institutional capacities for readily access to evidence by ministries of health in Kenya and Malawi. This work, initiated in September 2019, hopes to support the two ministries to strengthen their existing structures for research and knowledge gathering, synthesis, and sharing in order to readily access and use evidence as and when needs arise.

This article has been published by both the Star Newspaper Kenya and Standard Newspaper Kenya.

Dr Leyla Hussein Abdullahi, Research and policy analyst. African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP)

Related Posts